Arts

Icon Painting

Painting in the Old Rus appeared and developed in close connection with icon venerating, based on the doctrine of God's incarnation. The first icon in the Christian tradition was an image of Jesus, which miraculously emerged in his lifetime. It is the "Holy Face", or "Icon of Christ not made by hand", sometimes also called "Veronica's Veil", based on the legend of its creation. The image is said to have been imprinted on a wimple placed by Christ against his face. Icon is a means for the Orthodoxy to state it as a clearly visible truth. In a way icon is divinity conveyed in images and not in words.

Undoubtedly, icon is not a picture but a sacred object. Icons are expected to heal and work miracles. Some of them were considered to be of a supernatural origin. Yet the majority of icons were created by humans. Icon painters had to be people of high moral ideals and of true faith. Only people with a rich inner life and considerable intellect could create icons.

An icon does not represent what the painter sees before him, but a certain prototype. Reverence for an icon stems from reverence for its prototypes. Hence its unique artistic style that has nothing to do with other arts. It does not aim to produce just an aesthetic impression. Icons are destined both to reflect and evoke prayerful concentration and serenity in communication with God. It explains peculiar artistic devices used in icon painting, such as reverse perspective, a number of viewpoints within the space of an icon, hierarchic placement of objects depicted, etc.

Canonic types served as a point of departure. The artistry lay in their interpretation. Along with Christianity the Russian masters adopted Byzantium style and centuries old technique of painting. Later there developed local icon painting schools - in Novgorod, Pskov, Yaroslavl, Tver, etc. - each of them with certain painting peculiarities.

The highest peak of ancient Russian painting falls on the 14-15 centuries, due to such outstanding masters as Theophanes the Greek and Andrey Rublyov.

Theophanes the Greek was a remarkable artist, important not only as the author of outstanding paintings, but also as one who exerted a great influence on Russian art in the years when its basics were being laid. His art - passionate, dramatic, wise, austere, at times tragically intense and frequently lofty left a deep impression on his contemporaries. Few of the great master's works have survived. They can be seen in Moscow's Cathedral of the Annunciation. These are icons of the Deesis Range representing Christ Pantocrator (Almighty), the Virgin, St. John the Forerunner, the Apostles Peter and Paul, St Basil the Great and St John Chrysostom, all the saints shown as entreating the Lord to remit the sins of humanity. He used dense, opaque coloring, similar to examples of Byzantine panel painting.

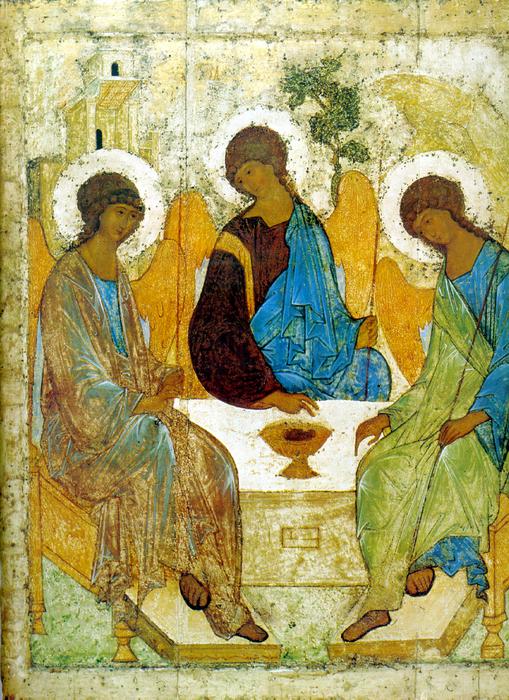

Andrey Rublyov who played a great role in laying the foundations of mature Moscow icon painting, owed much to Theophanes the Greek, his teacher, whose beautiful colors and pure forms he inherited. Yet, Rublyov's lyrical gift made him the antipode of Theophanes, whose somber, dramatic images were always alien to him. To Rublyov God was not the terrifying and merciless force he was to the ordinary medieval mind. Rublyov humanized God and made him seem closer to the world. Rublyov's purity of heart is reflected in his translucent images with no trace of either the excessively fanciful touches of Romanesque art or the exaggerated expressiveness of Gothic paintings. The icons of Rublyov radiate an aura of exceptional gentleness. His Christ, his Paul, his archangels are endowed with an irresistible charm, a gentleness in which there is no trace of Byzantine severity. At the peak of his powers Rublyov created his most famous icon, that of the Trinity (1422 - 1427) in memory of St Sergius of Radonezh. This icon exemplifies the simplicity of his skillful style able to transcend pictorial constraints with spiritual ideas. The icon renowned for its highly lyrical, rhythmical and symbolical quality was created by the master as a token of spiritual unity and accord of the Russian people.

The icons and frescos of Moscow painters of the 15-16s centuries are characterized with gentle painting and harmony of palette. Their artistic devices found development in Dionisii's icons and frescos, attractive for their delicate proportions, festive colors and the balance of composition.

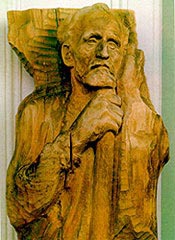

Ancient Russian sculpture existed in the form of decorative wood carving and was prevailingly polychromatic (similarly to European sculpture, it was painted with tempera or oil colors).

Sculptured were mainly images of saints, with most attention paid to the faces, while the figures were covered under the dresses and thus looked flat.

Western influence

From the middle 16th century Russian icon painting falls under the influence of Western European pictorial art. Courtier icon painting school turns to European plot schemes.

The late 16th - early 17th centuries marked the development of the Stroganov's school that consisted mainly of tsar's court masters and was peculiar for its finesse of palette, elaborate attention for detail and tendency for decorativeness and 'prettiness' of painting.

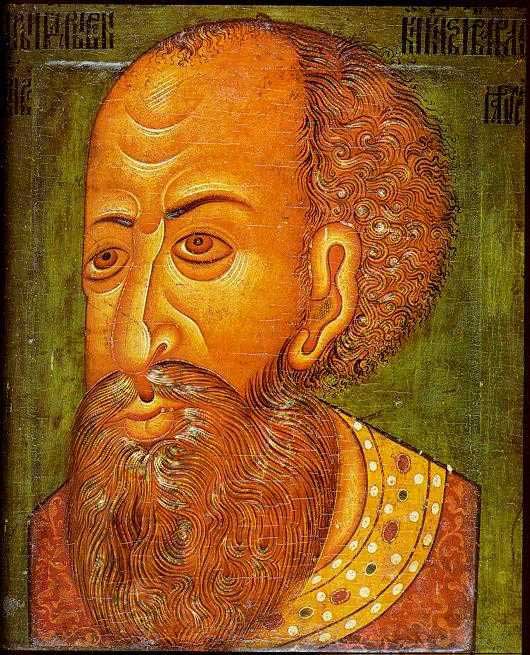

The second half of the 17th century saw the appearance of icons with elements of European painting: oil paints, endeavors of light and shade modeling and greater verisimilitude in picturing people and nature. The most famous representative of this trend is Simon Ushakov (17 century). This was also the time of first attempts of creating a secular portrait - the so-called parsunas.

Renewed interest for icons as a great art developed in the early 19th century in connection with clearing of darkened ancient icons and revealing their genuine palette. Artistic principles of icon painting were creatively applied by both individual Russian (V. Vasnetsov, M. Nesterov, K.Petrov-Vodkin) and foreign (A.Matiss) artists and avant-garde schools.

Academism

In the 18th - early 19th centuries the pictorial art in Russia driven by cultural demands of the society, embraces all the major stages of Western art: baroque, classicism and romanticism. The leading role in this process belongs to foreign painters and sculptors invited to Russia, but already during the reign of Elizabeth I there appear gifted and highly skilled domestic masters. From the mid 18th century academism becomes the prevailing trend, with its austerity of drawing, strict rules of composition, conventionality of palette, use of scenes from the Bible, ancient history and mythology. However the greatest achievements of this period were gained in the portrait rather than in historic painting (A.Argunov, A.Antropov, F.Rokotov, D.Levitsky, V.Borovikovsky, O.Kiprensky). The first outstanding Russian master of sculptural portrait was F.Shubin.

The hey-day of the academic school falls on the first half of the 19th century. The paintings by Karl Bryullov are remarkable for the blending of academic classicism with romanticism, the novelty of subject matter, dramatic effect of the plastic and chiaroscuro, complexity of composition and brilliant virtuosity of the brush. The first to enter the path of free and unconventional creation, he aroused deep interest in the audience and raised the social role of Artist. Alexander Ivanov's works bearing the flavor of his self-giving to servicing the ideal, outdo the stereotypes of academic technique. Later the best traditions of academism find their development in the colossal historic pictures by G.Semiradsky.

National theme

Social aspirations of the 1860s - 1870s wake up the artists' interest in folk life. The year 1872 saw the foundation of Association of traveling exhibitions as a counter to the Academy of Fine Arts. The famous Wanderers (among them Ilya Kramskoi, G.Myasoedov, K.Savitskiy, I.Pryanishnikov, V.Makovskyi, I.Yaroshenko and V.Perov) resort to genre painting acquiring exposal character in their works.

The turning to national themes resulted in an unheard blossoming of historic and military painting. Genuine masterpieces of these genres were created by V.Surikov, Ilya Repin, Nikolai Ge, V. Vasnetsov, V.Vereshchagin, F.Rubo.

Uncoined composition and historic truthfulness are combined with skillful use of plentiful artistic devices in interpretation of historic images and events. The historic theme has a powerful sounding in sculpture as well (P. Antokolskyi).

These years saw the opening of the first national galleries; works by Russian artists start appear regularly at international exhibitions and foreign art shows.

Attaining creative independence in the 19th century, Russian painting develops in the tideway of European fine arts. Genre painting gives way to landscape. Endeavors to render air and light and working plain air, which are characteristic of impressionism, can be seen in paintings by F.Vasiliev, I.Levitan, V.Polenov, V.Serov, K.Korovin, V.Kuinji and A.Arkhipov. Symbolism, neoclassicism and modern have a considerable influence on A.Vrubel and artists from the World of Art (A.Benua, L.Bakst, E.Lansere) and the Blue Rose (S.Sudeikin, N.Krymov, V.Borisov-Musatov)

Social realism and modern

In the 1930s avant-garde artists suffer from the Soviet ideological pressure; they are more and more often accused of formalism and indulgence of the bourgeois tastes.

Surrender to the official artistic doctrine of social realism impairs art of many Russian painters. However, the works of I.Grabar, P.Korin, A.Deineka, M. Saryan, K.Yuon, M.Grekov, M.Gerasimov and M.Plastov represent felicitous combination of realistic traditions with achievements of modern - mainly those of impressionists and Cezanne.

The 1960s mark the revival of the Russian avant-garde. International acknowledgement is gained by the art of O.Tselkov, V.Nemukhin, I.Shelkovsky, O. Rabin, A.Zverev, M.Shemyakin, L.Sokov, E.Neizvestnyi. Some of these artists followed or restored the principles of the already existing schools and trends, while others created new ones, such as conceptualism (Ilya Kabakov) and SotsArt (Komar, Melamid).

"Allowed', yet not para-governemental part of the Soviet art of the 1960s is represented by the artists of the so-called 'austere style' (T.Salakhov, S.Popkov).

Russian Avant-garde Art

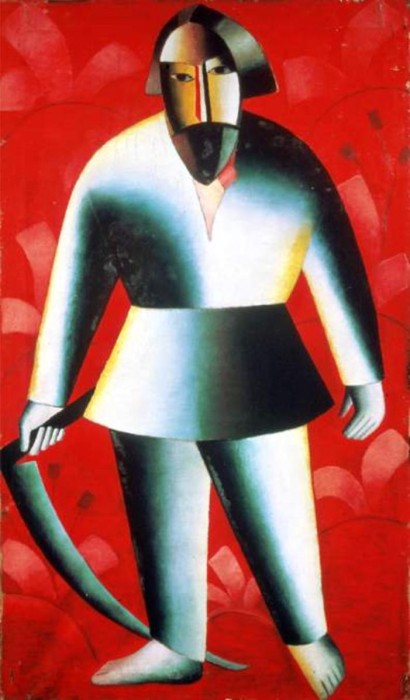

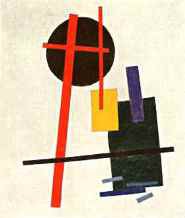

Russian avant-garde is a common term denoting a most remarkable art phenomenon that flourished in Russia from 1890 to 1930, though some of its early manifestations date back to the 1850s, whereas the latest ones refer to the 1960s.

The phenomenon of Russian avant-garde does not correspond to any definite artistic program or style. This term was assigned to radical innovative movements that started taking shape in the prewar years of 1907–1914, came to the foreground in the revolutionary period and matured during the first post-revolutionary decade.

The phenomenon of Russian avant-garde does not correspond to any definite artistic program or style. This term was assigned to radical innovative movements that started taking shape in the prewar years of 1907–1914, came to the foreground in the revolutionary period and matured during the first post-revolutionary decade.

Various trends of avant-garde art were united by an emphatic breaking-off not only from academic traditions and eclectic aesthetics of the 19th century, but also from the new art style of modern, which at that time was upmost in all the art spheres from architecture and painting to theatre and design. Russian avant-garde discarded the cultural heritage of the past and rejected continuity in artistic creation. At the same time it combined both destructive and constructive urges: the spirit of nihilism and revolutionary aggression along with ground-breaking energy targeted at creation of something totally new in art and other spheres of life.

In different stages these innovative tendencies were referred to with a variety of terms, such as "modernism”, "new art”, "futurism”, "cubo-futurism”, "suprematism”, "constructivism”, "left art”, etc. Just a few years before that nothing in Russian art heralded such a dramatic switcheroo: in the late 19th century Russian official fine arts remained within academic frames. It probably accounts for the fact that such artists as Borisov-Musatov (1870—1905), Valentin Serov (1865-1911) and Konstantin Korovin (1861-1939), though rather traditional by Western standards, were considered quite innovative in this country.

The direction of avant-garde movement, i.e. transition from natural to notional, from sophistication to simplification and pruning, from modernist refinement to primitivism, was similar to that in European art. Analysis reveals that the sources of this tendency lie beyond the Russian art tradition. Unlike in France or Germany, where the avant-garde art development was backed up and encouraged by various philosophical, aesthetic and psychological theories, in Russia it was prompted by the pre-revolutionary atmosphere and the activities of patrons of art and enthusiasts who steered the national art life into the tide of European culture (like Sergei Diaghilev with this Ballets Russes, for instance).

The direction of avant-garde movement, i.e. transition from natural to notional, from sophistication to simplification and pruning, from modernist refinement to primitivism, was similar to that in European art. Analysis reveals that the sources of this tendency lie beyond the Russian art tradition. Unlike in France or Germany, where the avant-garde art development was backed up and encouraged by various philosophical, aesthetic and psychological theories, in Russia it was prompted by the pre-revolutionary atmosphere and the activities of patrons of art and enthusiasts who steered the national art life into the tide of European culture (like Sergei Diaghilev with this Ballets Russes, for instance).

The pioneers of Russian avant-garde, such as for example Natalya Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, by 1910-1911 already found themselves in the tideway of the most novel European currents, on the level of the most daring and ground-breaking approaches in painting. The most innovative "peasant” canvasses of Natalya Goncharova came concurrently with or right after the famous "negro” works by Picasso. By the mid 1910s the role of avant-garde in art passed on to Russia. From that time everything most pioneering was created in Russia or by natives of Russia.

The connection between the aesthetic revolution and social upheavals of the 20th century is obvious. Russian avant-garde which did not outlast long the Social revolution, was undoubtedly one of its ferments. On the other hand, the firstling of the normative ideological art, Soviet realism, was a direct outcome of this revolution.

Russian Sculpture: History Outline

Since in Old Rus’ art served exclusively religious aims and the Orthodox Church disapproved of sculpturing human figures, there was no Russian sculpture in the real sense of the word before epoch of Peter the Great. Artistically poor cast crosses, sacred images, icon settings, carved figure iconostases, and painted carved icons that emerged in former Novgorod lands under the Western influences and were devoid of any artistic significance are the only examples of rudiments of old Russian sculpture.

Those rudiments had seen no development by the 18th century and Peter the First, when starting the Russian fleet and artillery and requiring sculpture masters hired foreign casters and sculptors who were to teach their art to the Russians. But both under Peter the First and his successors sculpture developments long stayed in foreigners’ hands.

The Academy of Sciences open under Catherine the First had an arts department where sculpture was taught, yet it did not contribute much to progress of Russian sculpture. Still masters from abroad were employed to meet the demands of the imperial court. Out of those overseas sculptors there stood out Count Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli, famous for his statues in Rococo style. Only upon the establishment of Arts Academy first Russian sculptors started to grow up under the guidance of the talented sculptor Nicolas-Francois Gillet from Paris. Covering the requirements of noblemen who following the Western fashion wanted to have works of sculpture at their disposal, sculptors of Catherine’s epoch were engaged in creating marble monuments and manner busts that were in great demand.

Most remarkable of the first Russian sculptors were the gifted Fedot Shubin and Mikhail Kozlovsky, who worked in reign of Catherine the Second, and Boris Orlovsky from Alexander’s epoch. Having got classical education and perfected their skills in Europe they adhered to classical technique and French style reigning in Western Europe in those years, and yet at the same time they managed to add something independent and original into their creations.

On the contrary, Feodosy Shedrin, Ivan Prokofiev, Fyodor Gordeev, Stepan Pimenov and Ivan Martos whose activity fell on the reigning of Alexander the First and beginning of Nicholas the Second’s reign, though having good skills and technique slavishly stuck to the boring and impersonal classical style predominating at that time.

The art of sculpture saw some enlivening under the reign of Nicholas the First. Count Fyodor Tolstoy who was heading the Academy of Arts for over thirty years aroused interest of the capital public in art and set medalist craft on the artistic basis. Yet, the major merit was that of Emperor Nicholas the First who loved and patronized arts and greatly helped up promote the art of sculpture by making large-scale governmental orders. Numerous orders were mainly fulfilled by Russian sculptors, such as Samuil Galberg, Ivan Vitaly, Nikolay Ramazanov, Alexander Loganovsky, and Nikolai Pimenov. Those sculptors limited by definite orders and brought up by the Academy with tendency for imitation and pursuit of outer beauty showed little free creativity and yet some of them timidly started to join the growing aspiration for realism and national roots.

Faint attempts of this kind can be seen on some works by Pimenov and Loganovsky. The new tendency clearer expressed itself in creations of Pyotr Klodt who had not studied at the Academy: the horses set up on the Anichkov Bridge in 1850, monument to Ivan Krylov and statue of Emperor Nicholas the First. Those statues replaced imitation of antiques, allegories and various stratagems with intent study of nature. They brought truthfulness and authenticity into art of sculpture. The new approach that started under Nicholas the First fully developed during reigning of Alexander the Second.

Upon changing the organization of artistic upbrining in the Academy, Russian sculptor already less estranged from life, and less limited by the governmental guidance became more independent and following the overall tendency closer to the national roots. One of the representatives of this new generation of sculptors, who tried to serve realism and the national spirit, was Fyodor Kamensky, whose works were clear evidence of his determined attempt to take a free independent path and cut the strings of limiting academic classicism. During the last 40 years of the 19th century this trend asserted itself in Russian sculpture.

However, on the whole the new sculpture was less national than new painting and architecture. Its best works created by Mark Antokolsky, Fyodor von Bock, Vladimir Beklemishev, Parmen Zabello, Robert Zaleman, Nikolay Laveretsky, Alexander Opekushin, Matvey Chizhov, Alexander Snegirevsky, and Ilya Gintsbourg belonged in the pan-European type. Only small groups and statuettes by Artemy Auber, Eugene Lanceray, and Nikolay Liberikh give talented and realistic images of Russian living.

In the tumultuous 20th century sculpture became very contradictive and was often associated with various modernist streams and formalist experiments of cubism (Alexander Arkhipenko), constructivism (Naum Gabo, Lazar Pevzner), surrealism, abstract art and so on. Modernist trends were consistently opposed by soviet sculpture developing in the framework of Social realism.

Its development was inseparable from Lenin’s plan of monumental propaganda, on the basis of which the first revolutionary monuments and memorial plates, and later many noteworthy monumental sculptures were created Ivan Shadr, Vera Mukhina).

Tragic events and heroic deeds of the war period found especially vivid reflection in memorial constructions of the 1940-70s (Yevgeny Vuchetich and others).

Acute feeling of modernity and search of ways for renovating the sculpture language were typical of the sculpture of the 1950-70s. Modern sculptors in Russia are open to world-wide tendencies and are free to express themselves. Some of them have gained international fame:Mikhail Shemyakin, Ernst Neizvestny, Alexander Rukavishnikov and Zurab Tsereteli.

Russian Style in Architecture – What is it?

What features of the modern Russian architecture pertain to the authentic Russian tradition?

Already in the late 19th this question stirred up the minds of zealous researchers of Russian architecture. Under the influence of the Slavophil and Narodnik ideas popular at that time they created a new style, which was called pseudo-Russian and which should not be confused with the genuine Old Russian style. The authors of the "pseudo-Russian style” freely interpreted decorative motifs of the architecture of the 16-17th cc. when creating terems (tower-chambers) with arched ceilings, narrow windows framed with wrought-iron lattice, and carved "big-bellied” columns. St. Basil’s Cathedral (built in the 16th century and many times remade afterwards), a mixture of Gothic, Old Russian, Byzantine and Indian styles was taken as a paragon and a model for imitation. The motifs of the fairy "Heavenly City” used in St. Basil’s Cathedral were repeated in this or that way in all the pseudo-Russian Moscow buildings, such as Pogodinskaya Izba (Peasant House) (1856), State Universal Store (GUM) (1893), the State Duma (Lenin Museum) (1892), State Historical Museum (1872), and others.

Izba, the National Folk Abode

Izba, the famous Russian log hut is probably the most optimal and salubrious variant of a dwelling house for the Russian climate. Our forefathers used to build log  houses easily and dexterously, gathering altogether and using only spades, axes, ropes and knives (and no nails at all!) as instruments. The timber (mainly pines and fir-trees) for building was selected following certain beliefs: one could not build anything from a tree grown by somebody, from a too gnarled tree, or from a tree that fell wrongly (i.e. northwards or on the crowns of other trees) when being cut. Usually the plan of the house was marked out right on the ground with the help of a measuring rope; then the builders dug out a pit 20 to 25 cm deep, added some sand to cover this area and put the first "fourth” – a quadrangular timber set along the perimeter of the future house. There was a custom to put wool, frankincense and coins under the corners so that the house would stand longer and living in it would be wealthy and healthy.

houses easily and dexterously, gathering altogether and using only spades, axes, ropes and knives (and no nails at all!) as instruments. The timber (mainly pines and fir-trees) for building was selected following certain beliefs: one could not build anything from a tree grown by somebody, from a too gnarled tree, or from a tree that fell wrongly (i.e. northwards or on the crowns of other trees) when being cut. Usually the plan of the house was marked out right on the ground with the help of a measuring rope; then the builders dug out a pit 20 to 25 cm deep, added some sand to cover this area and put the first "fourth” – a quadrangular timber set along the perimeter of the future house. There was a custom to put wool, frankincense and coins under the corners so that the house would stand longer and living in it would be wealthy and healthy.

Terem

Unfortunately, not many really old wooden terems have come to us: time and fires have done their part. In the olden days noble and rich people used to live in splendid terems (tower-chambers) which had a great variety of multi-level premises and annexes, such as inner porches, passages, staircases hid in the walls, and so on. Usually the owners of the house did not stint decor: the terems were lavishly decorated with painting, carving, and were even crowned with gilded roofs, like temples.

National Decor: Carving and Glazed Tile

Artful wood carving was a distinctive original decoration of Russian wooden buildings; and that is one of the few traditions kept alive and remaining popular till date. There was relief carving and "through” carving.

The technique of glazed tile spread in Russia only in the epoch of Peter the Great, though much earlier, from the Kievan Rus, colourful glazes were used, and before it, relief drawings on terracotta clay (certainly, with pagan motifs) were popular.

Where Can One See Authentic Russian Style?

Not so many authentic Old Russian buildings have been preserved in Moscow; naturally, the majority of them are located in the centre. First of all this is the carved white stone Terem Palace of the 17th century in the Kremlin. A construction of almost the same time has survived in Krutitsy Metochion: the gates with an outstandingly beautiful red-brick terem decorated with glazed tiles. Besides, Moscow has some old stone chambers preserved: this is certainly the famous Palace of Facets (15th c.) in the Kremlin, chambers of the Old English Court (16th c.) and chambers of the boyars Romanovs in Varvarka Street, where a branch of the Historical Museum is housed nowadays.

Perm Animal Style

Perm animal style is one of the pearls of ancient ethnic culture; its artifacts featuring mythology of the bygone pagan times surprise with their complicated and fanciful harmony. These stylish metal castings found in the Ural inspire scientists and artists to try to fathom the mysteries they harbour.

Ural is a huge territory situated in the geographical centre of Russia and linking Europe and Asia. The word ‘Ural’ is translated as a "Stone belt’. This land of original ancient culture is the native place of Finno-Ugric tribes. In olden times Kama River served as a trading way connecting the ancient civilizations of the East and the local Ural tribes.

Those tribes left unique specimen of ancient art of metal castings representing animal images that obviously served as sacred totems. The roots of the animal art style that developed in the 7th – 5th cc B.C. go back to the cave and rock paintings and carvings of the Paleolithic and Neolithic ages.

The Perm animal style is represented by hundreds of findings of tracery bronze and brass plates, figurines, pendants with relief pictures of animals, birds, fish, fabulous creatures, and people. The most widespread are images of elks, bears, horses, swans and ducks. The duck was especially honoured by the local tribes: a legend says that soil appeared on the Earth thanks to this bird. A right-angled plate with the image of a bear has become symbolical of the Perm animal style. One of the major peculiarities of this style is the intricacy of images.

Researchers resort to myths and rites of Komi, Udmurt, and Lapp tribes to explain the meaning and the purpose of the artifacts of Perm animal style. All the findings can be relatively divided into two big groups.

One part of them is represented with ‘figurines of beasts and birds’ that are found in all types of archeological monuments, such as burial grounds, sites of ancient settlements, and places for worshipping. The analysis of their location in the burials shows that alongside with beads and various pendants these articles served as decorations and after the death of their owner were buried with him/her as ‘accompanying implements’. No doubt the decorations fulfilled not only the aesthetic function but also implemented sacral meaning.

The decorations in animal style are made of various copper alloys and are quite diverse. Many of them after the moulding were polished, blanched, and chiseled. Most frequent are decorations with images of birds, swimming (swan and duck), forest (heath-cock and wood-grouse), and raptorial birds pecking their prey. Numerous and diverse are horse pendants. Some decorations are based on the images of bears and fur-bearing animals, such as sables and martens. The decorations are characterized with realistic images. Only the image of the ‘yelling bird’ has no prototype in nature. The figurines were probably used as tools for common magic and zoomorphic images played the role of protecting amulets.

The other part of animal style artifacts are various sacral plates with zoo- and anthrop-amorphous images and complicated compositions of them. The zoomorphic images include figures if flying birds, bears’ heads, pangolins and blends of various animals. The anthrop-amorphous images are humaniform idols, faces and plates featuring men-elks. They were all made by means of plain and semi-relief casting followed by engraving, embossing, and soldering of details. Lots of them have holes and claspers for hanging or stands.

The researchers unanimously agree that these plates reflect the ancient peoples’ perception of the universe and man’s place in it. That is why they were in collective property and played an important role in ancient rites. This can account for the fact why all the plates, unlike the decorations, were found in the settlements only, and mainly at monuments of cult, altars and sacred places.

The exception is figurines of flying birds which are also found in burial grounds. Those figurines obviously played a special role in the rite of burial, which reflected the ancient conceptions of death, soul, and afterlife. The Perm animal style is a bright example of the art epoch of the so-called ‘World Tree’, a universal concept that for a long time defined the model of the world. The art of this epoch tends to oppose the ‘lower’, negative and the ‘higher’, heavenly realms. In Permian compositions the ‘underground’ is symbolized by a fantastic creature of pangolin wearing a horn. The creature above the pangolin is called Sulde, a combination of features of a human being, an animal (elk is most common) and a bird, which represents the higher realm.

Certain repeated motives of the Perm animal style cannot but make you wonder, such as, for instance, elk-headed men, three-eyed goddesses, and birds of prey with a human face on the chest.

In the 10th century A.C. the Perm animal style degraded but left impact on the development of art of the Ural peoples: its traits were inherited and preserved in embroidering, weaving, fur mosaics, and wooden sculpture. Some modern artists resort to this style in search of interesting artistic solutions and some of them attempt to recreate and imitate the found ancient artifacts.

White Stone Architecture of the Old Rus’

The Old Rus’ has left us its amazing white-stone monuments of architecture; the magnificent cathedrals of Vladimir and modest churches of the Moscow Region, constructed of white limestone, embodied their epoch with the stone handwriting of builders, whose talent in those remote times could reveal itself mostly in erecting constructions of cult. With amazing accuracy they abated soft limestone to make wall blocks, flagstones for footsteps, socles and bases, window cases, fanciful figures, ingenious ornaments and even statues. Intricate carvings of ornamental décor on ancient cathedrals have stood the test of time for many centuries.

The Old Rus’ has left us its amazing white-stone monuments of architecture; the magnificent cathedrals of Vladimir and modest churches of the Moscow Region, constructed of white limestone, embodied their epoch with the stone handwriting of builders, whose talent in those remote times could reveal itself mostly in erecting constructions of cult. With amazing accuracy they abated soft limestone to make wall blocks, flagstones for footsteps, socles and bases, window cases, fanciful figures, ingenious ornaments and even statues. Intricate carvings of ornamental décor on ancient cathedrals have stood the test of time for many centuries.

Usually the term ‘white stone’ stands for light carboniferous limestone (from the Paleozoic Era), occurring in the central regions of European part of modern Russia. However, it is also often referred to sandstone, dolomite, and Volga limestone of Permian formation, as well as numerous sorts of limestone, travertine, and alabaster lying in Transdniestria. Consequently, a more general definition of white stone is any treatable white-yellowish matt surfaced stone, which is neither marble nor shell rock.

White stone was one of the basic building materials in Old Rus' and was of great historic importance as an expression of the state’s power and imperial ideology in the 12th -15th cc. It played a key role not only in the Old Russian Architecture, but in the history of the Old Russia as well.

Christianity came to Russia from Byzantium, but church building was performed ofplinthos (a special sort of broad and flat baked bricks) or in the mixed technology, «opus mixtum». The building methods used in Kiev, Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk, and all other Old Russian lands, but for Vladimir and Suzdal Principality, where white stone building was started in 1152. In the pre-Mongolian years 95 per cent of buildings in Vladimir and Suzdallands were built of white stone. The most emblematic and impressive white-stone churches are the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir (1158—1160, rebuild in 1186—1189) and the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin on the river Nerl near Bogolyubovo Village of the Vladimir Region (1158).

In the 12th century, when white-stone building was launched in Russia, Byzantium was already weak and did not have any considerable power on the international arena. At the same time, in the epoch of Gothic and Romanic styles in the Western Europe building of various kinds of stone embodied the state power and imperial ideology, whereas brick was used only for minor secular constructions and churches in poor outlying districts. Hence, following the example of West European building, Suzdal  princes shifted to white-stone technology, expensive and unreliable, but "imperial”.

princes shifted to white-stone technology, expensive and unreliable, but "imperial”.

White-stone building became one of the major steps of the Old Rus becoming one of the leading European powers, the process, interrupted by the Mongol invasion for a long time. However, even in the hard times of the Mongol Yoke the builders of the Old Rus went on using white stone, which probably became one of the factors that helped the Vladimir-Suzdal Princedom in preserving its spiritual independence and resurrecting under the new name of Muscovy Rus’.

When Moscow became the basis for uniting the disconnected Rus into a single state, the construction of monumental buildings was of great importance. Therefore, churches turned to be monuments marking crucial facts in Russian history. Thus, for example, the famous St. Basil Cathedral (1555—1560) was a celebration of Ivan the Terrible’s taking of the Kazan Khanate.

In the late 15th century, when masters of the West European Renaissance completely shifted to the far more reliable, economical and practical brick building, the expression of the state power in stone had no sense any longer. Then Russians also switched to brick building. The last remarkable Old Russian white-stone church was the Dormition Cathedral (1475—1479) in Moscow. However, wide use of white stone did not stop, since it was used everywhere for bases, ground floors, and elements of architectural decor. Stone carving in Russian architecture reached enormous heights in the 16th- 17th centuries. White-stone carving was used both for church and secular buildings. Vivid examples of Russian stone carving art can be found in chambers and towers of the Moscow Kremlin. The Faceted Chamber (1487—1491) was decorated with intricate carved platbands in the 17th century, and the Teremnoy (Tower-Chamber) Palace is one of the treasures of Russian white-stone carving. The craftsmanship of Russian stone carvers manifested itself not only in Moscow, but in other towns and regions as well. Thus, carved stone details can be also seen in Yaroslavl churches of the 17th century, the Convent of the Presentation of the Mother of God in Solvychegodsk, etc.

Fanciful carved ornaments and bas-reliefs are the greatest mystery of white-stone Old Russian architecture. It has come down to us only in fragments, mainly on the miraculously preserved St. Dmitrius Cathedral in Vladimir and St. George Cathedral in Yuriev-Polski. There are various hypotheses on the symbolic meaning of images depicted on the bas-reliefs of the St. Dmitrius Cathedral. Unfortunately, in the span of eight centuries that have passed since the creation of the church, Russian people somehow lost this beautiful legend, and so historians can only speculate about it now. Some explain the white-stone carving ornamentation as a peculiar expression of nostalgia that people of that time had about the heritage of paganism past recovery. There is also an option to account for these ornaments with the Roman, Byzantium, Scythian and Iranian, Celtic or Slavic pagan influence.

Richest realm of animal and fabulous images settled not only on the walls of churches, but also penetrated inside, to the capitals. Most popular were the images of gryphons, lions and leopards. The lion and leopard symbolized the power and strength of Vladimir princes. Gradually they took place in heraldry of great princes. The image of the fanciful gryphon bore a triumphant, winning meaning. Along with these adopted motifs in white-stone sculpture there appeared folklore and apocryphal images, such as dragons, various birds, and Kitovras, which speaks of broad social content of white-stone sculpture images. Folk roots of sculpture most strongly manifested in the floral treelike ornaments.